Been There, Done That

AN ARTIST’S RECKONING WITH BEING VS. DOING

BY IVAN CASH

As a child, I dreamt of being featured on the front page of The New York Times, probably for similar reasons kids these days want to be social media influencers: so many of us feel alienated and alone, craving recognition and connection; We all want to matter. Having been bullied with anti-Semitic undertones throughout childhood, the idea of having a voice in the world assured me of both mattering and re-writing the bigoted script I’d grown up with.

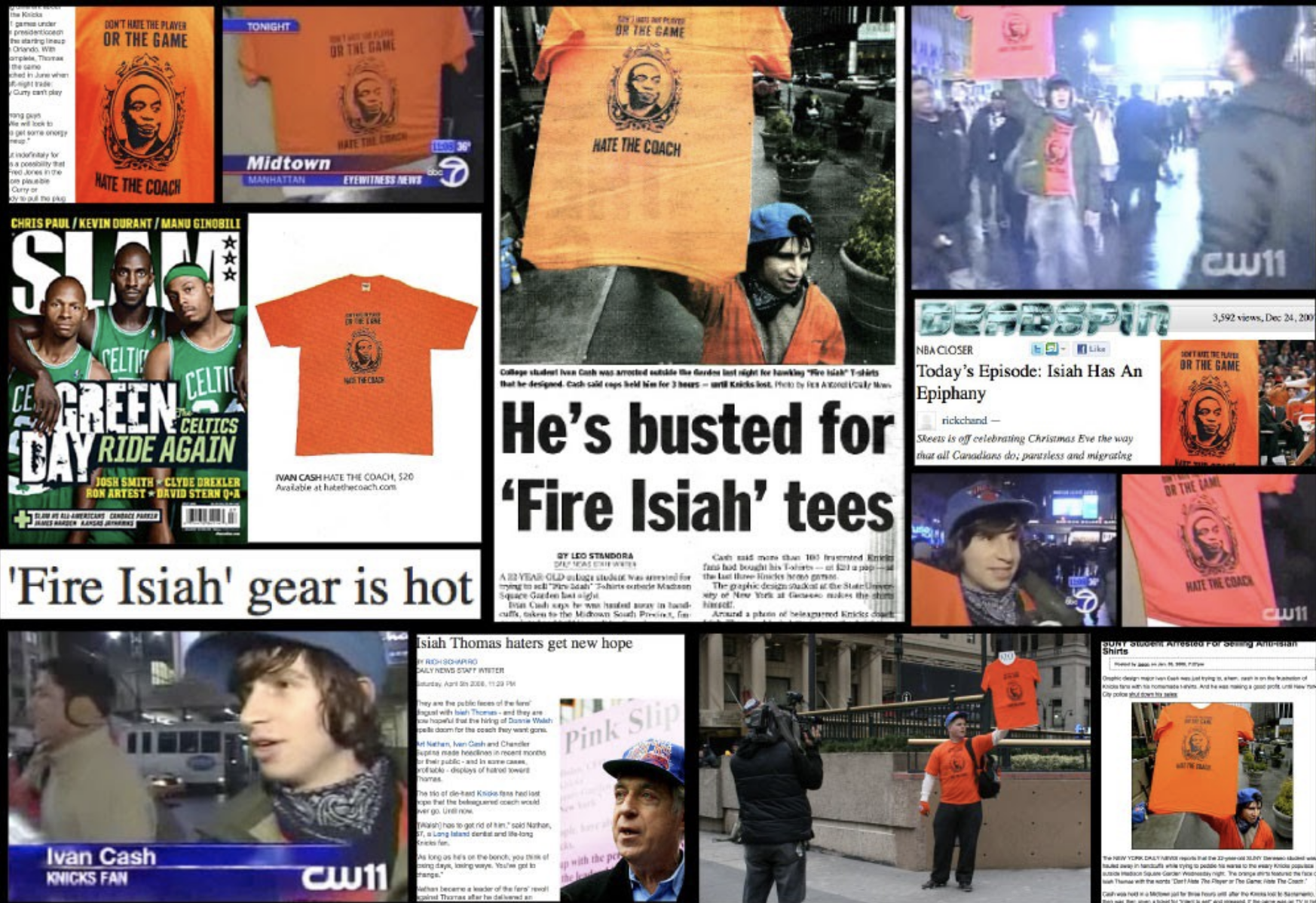

I got my wish—sort of—at age 16 when my letter to The Ethicist got published in the Times and soon after was picked up by Reader’s Digest. Five years later, I’d receive more press coverage for being arrested in New York City, selling hand-printed t-shirts about my favorite basketball team, the New York Knicks. News of my arrest quickly went viral and I got my first job in advertising as a result.

While advertising paid my bills, my primary creative output went towards subverting mainstream cultural narratives with passion projects tackling themes ranging from censorship and wealth inequality, to exploring human connection through letter writing, portrait drawing, and street interviews. Many of these projects went viral, and by the end of my 20s, I’d collected prestigious awards, toured the world speaking at industry-leading creative festivals, and collaborated with Fortune 100 brands. Finally, I mattered.

But the recognition, as good it felt, was always fleeting. You could say I’d “done” a lot, but my goal posts kept growing further away. As soon as I reached one long-coveted benchmark, a new one would appear in the distance. Simultaneously, our culture was changing. Resumes, artistic portfolios, and actual experience became less relevant, in favor of the sheer number of social media followers one has. This conflux of factors felt dizzying, and impossible to keep up with. Why, if I’d accomplished so much, did I still feel incomplete?

To begin answering this question, I had to look past doing more and towards simply being. Whereas “doing” speaks to creating, building, and taking action, “being” equates to finding meaning, contentment, and acceptance in the unaltered, immediate moment. In the spirit of the topic at hand, this essay has taken over a year to complete. During this time I ran my first marathon and remodeled my first home. I’ve tried to be with the text rather than rushing to finish it.

So how does a person, in 2022, focus on doing—embracing a life of passion and striving to reach their true potential, while simultaneously being—staying grounded, present, balanced? This is the question I’m setting out to answer.

Fifteenth-century Zen monk and poet Ikkyu gave a simple response: “Having no destination, I am never lost.” Plainly stated, Ikkyu felt free just to be, seemingly unperturbed by the need to plan or set goals for himself. He didn’t need to be anywhere other than exactly where he was and he presumably trusted the universe would conspire in his favor.

Five centuries later, American historian Howard Zinn retorted, “You can’t be neutral on a moving train,” by which he meant we can’t and shouldn’t passively accept things as they are. The moving train in Zinn’s analogy is society, which is always evolving and steaming ahead. We are thrust into the politicized realm of humanity simply by being alive, he asserts, and non-doing dismisses this essential truth.

Recent social and political movements like Black Lives Matter and #MeToo have inspired artists and everyday citizens alike to take responsibility and do something in the fight against injustice. For the record, I’m all for this. However it’s not always clear how to channel such passion or rage beyond, say, reactive social media posts. Is this the action Zinn was getting at?

Portrait of Ikkyu (15th Century)

In the 1990s, a subversive manifesto called Culture Jam by Kalle Lasn critiqued corporate culture, prompting, “Next time you’re in a particularly soul-searching mood, ask yourself this simple question: What would it take for me to make a spontaneous radical gesture in support of something I believe in?” Reading this book in college, I felt like Lasn was speaking directly to my soul. Devouring page after page, his words cycled through my mind like a biblical text, inspiring long, devoted hours on creative projects designed to both disrupt and remedy our monotonous culture.

These projects would grow in scope and ambition over the years, each more audacious than the last. Some turned into books, others into street signs, and more still into films, landing their way into museums, libraries, film festivals, and most thrilling—the front pages of the internet. Much like street art, making art for the internet doesn’t require asking for permission or waiting for hierarchical approval like a fellowship or grant. It’s a truly democratized art form, presenting the ultimate canvas and an unlimited audience.

After over a decade of nonstop output, however, the energy of these independent projects began to shift. They’d always had a Sisyphean flair to them, but what was once enthralling—the challenge of creating something new from absolutely nothing—eventually became exhausting. I’d always made a point to practice self-care, mainly through therapy and attending annual silent meditation retreats (which I treasure) but these activities, in spite of supporting my being, were, in their own way, a perverse form of doing.

Sisyphus, painting by Franz Stuck (1920)

By the time a small team and I launched a Kickstarter campaign for IRL Glasses (a prototype of glasses that block screens) in 2018, I was low on fumes but able to channel passion for the project to bring it to the finish line. We launched IRL Glasses, hoping it would hit a cultural nerve, and boy, did it! The launch elicited unfathomable press coverage and internet buzz. From Wired.com to the front page of Reddit and Product of the Day on ProductHunt. We sold over 2,000 pairs of IRL Glasses in just 30 days, with backers drawn to the promise of taking solace from their devices. Whilst basking in our success, the ugly truth was that my team and I were spending a sacrilegious amount of time glued to our own screens, in support of the campaign. We all burnt out and the irony, like a screen, was hard to turn away from.

I don’t think this depleted feeling was unique to us or our project however; I know an unsettling number of peers who admit to being just an exhale or stumble away from total burnout. In today’s hyper- connected, productivity-hack obsessed world, exhaustion is the ticket for entry. And in this world, it’s completely normal to bake a loaf of sourdough and post about it on social media before taking the first bite or go on a run while listening to an audiobook at 1.5x speed. We’re so inundated by gamified metrics that we ride Peloton to earn digital badges and covet blue checkmarks signaling one’s voice is worth listening to. (Having unknowingly relinquished my own blue checkmark after changing my Twitter username, I’d be lying if I said it didn’t plague me to this day.) Have these ‘doing’ signals become our religion?

Alas, “today we’re human doings, not human beings,” reflects contemporary Buddhist teacher Tara Brach.

With social media bequeathing everyone a virtual megaphone, the implicit expectation seems to be: you better say or do something with it or, at least, take note of what others are doing. This enormous pressure to participate means anyone who dares take a break (or worse, delete) their social media account does so at the risk of obsolescence. This has massive ramifications: “If we don’t know how to pause or arrive in the moment,” Brach explains, “then our way of living becomes automatic and shallow.”

Saturated in a culture of endless noise, pleas to engage, and “do more” brings to mind Buddhism’s second noble truth, which states the cause of suffering is our clinging to desire. According to this teaching, if we could simply curb our cravings and just be, our suffering would secede. This begs the question, how would a spiritual teacher like the Buddha relate to our frenetic-paced culture? Would his unique perspective have stood out against the cacophony of hash-tagged, celebrity adorned, brand-endorsed digital swirl? Would he have sat quietly under the Bodhi tree or turned into a social media influencer?

It seems pretty clear how technology hinders our ability to be fully present. But it’s also worth noting that the pursuit of greatness—the call to do big, courageous things in the world—often takes sacrifice and requires a particular flavor of intensity in its own right. One of the most accomplished basketball players of all time, the late Kobe Bryant, had strong thoughts on this matter: “If you want to be great at something, there’s a choice you have to make, there are inherent sacrices that come along with that. Family time, hanging out with friends, being a great friend, being a great son, nephew, whatever the case may be. There are sacrices that come along with making that decision.”

Kobe was known as a fierce competitor with an intense work ethic, often showing up at the gym hours before his 7am practice. Kobe understood it’s not possible to achieve the highest level of doing without compromising something. Staying balanced, prioritizing relationships, or simply being would be a fast track to mediocrity through this lens. Maybe some degree of burnout is just a necessary evil of success and creative excellence. If so, how do we decide when it’s worth doing at the cost of being? And just because we can do something, does it mean we should?

Game winner against the Miami Heat (2009)

Ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu, author of the 2,500 year-old text, Tao Te Ching, had a unique perspective on the matter: “Tao does not do, but nothing is not done. The gentlest thing in the world overcomes the hardest thing in the world... Teaching without words, performing without actions; that is the Master’s way.” Here, Lao Tzu seems to rebut the dualistic notion between doing and being. Rather than appearing as opposites, he implies doing and being are but two sides of the same coin.

“When we become truly ourselves,” adds Zen Master Suzuki Roshi, “...we just become a swinging door, and we are purely independent of, and at the same time, dependent upon everything.” While Suzuki Roshi’s sentiment doesn’t sound much like our goal-obsessed, sacrifice-everything-for- success modern mentality, it doesn’t outright denounce the idea of working hard to achieve our dreams either. What would it feel like to adapt a swinging door approach to life, with less rigidity and more flow for whatever we’re experiencing?

And herein lies the paradox of being... it often involves doing! Tropes typically associated with being like stopping to smell the roses, taking long walks on the beach, or even meditating all involve doing, yet often aren’t planned or performed for material gain. They point to how being isn’t always passive and doing doesn’t always have to feel so intense. Still following?

With this insight in mind, wildly ambitious creative ideas can, in theory, be mindfully birthed and acted upon. When I’m lucky enough to experience moments of deep creative flow and equilibrium, a sense of purpose and ease, transcendent of the mundane, emerges—where each passing moment feels alive with boundless energy.

As my mentor, Zen Student and Creative Executive, Jimmie Stone once told me, “You can still be mindful while climbing a mountain by focusing on one step at a time.” What if doing and being can, in fact, peacefully coexist?

Consider the performance artist Marina Abramovic’s work, The Artist Is Present. Her piece involved sitting silently across from an empty chair, as museum goers took turns sitting down across from her. No phone, no distractions, just eye contact and full-on presence. Over the course of three months, for eight hours a day, Abramovic locked eyes with 1,000 strangers, many of whom were moved to tears.

“Nobody could imagine...that anybody would take time to sit and just engage in mutual gaze with me,” Abramovic reflected.

The continuous line of audience members waiting to sit across from her, of course, proved otherwise. “The function of the artist in a disturbed society is to give awareness of the universe, to ask the right questions, to open consciousness and elevate the mind... Anything that is revolutionary is in front of your nose and it is never complicated,” she concluded. The simplicity of Ambamović’s performance exquisitely blurs the lines between doing and being.

Before disbanding South African apartheid, Nelson Mandela had been incarcerated for 27 harrowing years, mostly confined to a small cell with little to no human interaction. After his release, Mandela gave a speech in front of 100,000 South Africans declaring his intention for national peace and reconciliation with the very political leaders who had imprisoned him. He would eventually be elected President of South Africa in a peaceful transition of power. His story is one of resilience and perseverance, but also of unfathomable personal transformation.

When asked about his accomplishments, Mandela explained, “One of the most DIFFICULT things is not to change society—but to change yourself.”

From one of the most adorned humanitarian leaders the world has known, comes the admission that in order to do and make an impact on the world, we must first go inward and be. Personal transformation as a predecessor to external impact, yet the two are inextricably linked; being informs doing. And if we are, against all odds, successful in changing ourselves in this way that Mandela outlined, it could be argued we have a responsibility to ensure this change extends out for the greater good.

This sentiment is echoed by some of the great spiritual minds of the 20th century, including the late, indomitable Ram Dass, who eloquently stated, “The universe is perfect, including my desire to change it.” He envisioned a perfect world (being) inclusive of his actions and plans (doing) that can ultimately be achieved in a state that equally marries being and doing.

The late, prolific poet Mary Oliver added to this idea with, “Instructions for living a life: Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it.”

Oliver was advising we be curious and inspired, and then do something—anything—presumably to share our collected insights with others. And share these insights we must. A decade ago, I designed a tongue- in-cheek stencil about feeling creatively blocked. It read, “I’m not sure what to say.” I covered many of the sidewalks in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco with this simple message and was surprised when, days later, a response came in the form of another anonymous vandal offering reassurance: “It’s okay!”

This small interaction lit something up inside of me and I can only imagine the other artist was responding to conditions and acting on inspiration, moment by moment; doing AND being. This simple gesture created what I’d consider an exponential impact and makes me wonder what the world would look like if more of us attempted to do with a heightened presence and be with more intentionality?

In spite of all the external factors designed to distract and incline us towards solely doing, another reality is possible. What would a world where the gentlest thing in the world overcomes the hardest thing in the world look like? As we’ve seen through the aforementioned stories, lifting the paradoxical veil between doing and being is not only feasible, it just might be the answer for a more creative and inspired world; the kind of world we all want to live in.